ད་ཕན་རྒྱ་ནག་ནང་ཁུལ་དུ་། པེ་ཅིང་སྲིད་གཞུང་གི་འཛིན་སྐྱོང་ལ་ཕྱོགས་ས་སྒོར་མོ་ནས་ཁ་གཏད་གཅོག་མཁན་མང་པོ་ཡོད་པའི་ཁྲོད་ནས།

སྒེར་བའི་ཁེ་ཕན་བློས་བཏང་སྟེ་པེ་ཅིང་སྲིད་གཞུང་ལ་ཁ་གཏད་གཅོག་མཁན་མི་བཅུ་ནི། སྒྱུ་རྩལ་བ་ཨེ་བེ་བེ།(Ai Wei Wei) ཟིན་བྲིས་བ་གྲགས་ཅན་ཧན་ཧན།(Han Han) བོད་རིགས་རྩོམ་པ་པོ་ཚེ་རིང་འོད་ཟེར། གསར་འགོད་པ་ཧུའུ་ཧྲུའུ་ལིས།(Hu Shuli སྲིད་དོན་པ་རྒན་གྲས་ལིས་རུའུ།(Li Rui) ཐེན་ཨེན་མེན་ཨ་མའི་ཚོགས་པ་(Tiananmen Mothers)བཙུགས་མཁན་ཏིན་ཙི་ལིན།(Ding Zilin) སྲིད་དོན་པ་རྒན་གྲས་པའོ་གྲོང་།(Bao Tong) ༢༠༠༨ལོའི་བཅའ་ཁྲིམས་འབྲི་མཁན་ལུའུ་ཞའོ་པོའོ།(Liu Xiaobo) ཁོར་ཡུག་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་པ་ཧུའུ་ཅ།(Hu Jia) ཁྲིམས་རྩོད་པ་ཀའོ་གྲི་ཧྲང(Gao Zhisheng)་བཅས་རེད། འཛམ་གླིང་ཤར་ནུབ་ཀྱི་དོ་སྣང་ཅན་མང་པོས། སྤྱི་ཟླ་བཅུ་གཉིས་པའི་ཚེས་བཅུ་སྟེ། ལུའུ་ཞའོ་པོའོ་ལ་ནོར་ལྦེའི་ཞི་བདེའི་གཟེངས་རྟགས་སྤྲོད་ཉིན། པེ་ཅིང་གི་རྨི་ལམ་དཀྲོགས་མཁན་མི་བཅུ་བོ་འདི་དག་གང་དུ་ཡོད་མེད་ལ་སེམས་ཁྲལ་བྱེད་བཞིན་ཡོད།

Ai Weiwei

Born in 1957 in Beijing.

What makes him a dissident: Ai Weiwei’s emergence as a critic of the regime is recent. Until 2008, the avant-garde artist kept his political beliefs quiet and even served as a consultant on the construction of the Bird’s Nest stadium for the Beijing Olympics. But the government’s handling of the May 12, 2008, Sichuan earthquake, which left upward of 88,000 people dead, changed things for Mr. Ai. He started to attack the powers that be, using Twitter and his blog to question why so many schools collapsed on top of students and teachers.

Relationship with the government: Awkward, at least for the Communist Party. Mr. Ai’s international fame, and his status within China as the son of a celebrated poet, make it difficult for Beijing to simply throw him into a cell like other dissidents (although he was badly beaten in Sichuan by thugs he says were plainclothes police). That said, he seems to be getting closer to some invisible line, and was briefly under house arrest last month after he threw a “river crabs” party to celebrate the forced closing of his Shanghai studio. “Hexie,” the Chinese term for the crustaceans, sounds similar to the word “harmonious” and thus is popular online slang for those mocking President Hu Jintao and his stated goal of building a “harmonious society” in China. He is a signatory to Charter 08, the call for free speech and elections.

Impact: Hard to say. Mr. Ai is a hero among the small number of Chinese who go to cutting-edge art shows in places such as Munich and London, and his Twitter account has almost 60,000 followers. But the vast majority of this country’s 1.3 billion people probably couldn’t pick him out of a police lineup, despite his signature girth and beard.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: He was stopped on Thursday by security at the Beijing airport and told that he is not allowed to leave China.

Han Han

Born in 1982 in Shanghai, where he still lives.

What makes him a dissident: Mr. Han is the kind of dissident who could exist only in China in 2010. He is a professional rally car driver, teen heartthrob and bestselling novelist who also happens to be the world’s best-read blogger. It’s the latter of his three hats that causes the powers-that-be angst: His massive following (well over 300 million people have visited his personal blog) has read his sharp attacks on the Shanghai government over its hosting of Expo 2010 and his support for Google in its censorship battle with the central government in Beijing.

Relationship with the government: Mr. Han has – so far – shown an insider’s understanding of exactly what he can say about the country’s rulers without getting his blog cast to the other side of the Great Firewall (which blocks thousands of websites critical of the government). In an e-mail exchange with The Globe and Mail, he admitted that he had never directly questioned the Communist Party’s right to rule. “Otherwise, you wouldn’t have the chance to interview me,” he explained.

Impact: His power is difficult to measure. Of all the people on this list, he is the best known among ordinary Chinese. If he called for his millions of fans to meet him on People’s Square in Shanghai, it is likely a huge crowd would arrive to hear what he had to say. But it would also be the last time his blog would be easily accessible inside China.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: Mr. Han couldn’t be reached for comment for this article. When Mr. Liu won the Nobel Peace Prize, he put up a blog post with only two quotation marks and nothing in between them. It was all he thought he could safely say.

Tsering Woeser

Born in 1966 in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa. Married to dissident Chinese writer Wang Lixiong. Ms. Woeser is a Tibetan activist whose her father was a deputy general in the People’s Liberation Army stationed there.

What makes her a dissident: Among the many who denounce China’s rule over Tibet and call for the Dalai Lama’s return, Ms. Woeser is unique in that she says it in Chinese and from her apartment in Beijing. She and her blog, Invisible Tibet, became one of the go-to resources during the riots that swept the Tibetan Plateau in 2008, and the government crackdown that followed. Ms. Woeser was one of the original signatories of Charter 08. Her husband is a close friend of Liu Xiaobo.

Relationship with the government: Adversarial. Although Ms. Woeser grew up believing the Chinese army had “liberated” Tibet in 1959, she changed her mind as a young woman after reading the Dalai Lama’s autobiography. She says she was told by police that she can write about anything but Tibet, to which she replied she has no interest in writing about anything else.

Impact: Ms. Woeser’s most obvious impact is that her writings – and her network of sources – help to keep alive the Tibetan cause by passing information about what’s happening in Tibet to the outside world. Because she writes in Chinese, she also may soften the attitudes of some Han Chinese, the majority of whom see Tibet as a part of China.

Where she will be on Dec. 10: “I think I will be online together with Netizens who are interested in watching [the Nobel ceremony],” Ms. Woeser said in an interview this week. “This moment has special significance for us. It is a boost to the democratic movement, and encourages people who share the same spirit as Liu.”

Hu Shuli

Born in Beijing in 1953.

What makes her a dissident: She would probably cringe at the term, actually. Ms. Hu is a journalist to the core, as were her mother and grandfather. But telling the truth in China can make you a lot of powerful enemies. In 1998, Ms. Hu founded the groundbreaking newsmagazine Caijing, which quickly set a new standard in Chinese journalism. Although nominally focused on business journalism, Caijing also covered general news, and won plaudits for its critical coverage the SARS crisis in 2003 and last year’s riots in Xinjiang. Ms. Hu left Caijing last year after the publisher began pressuring her to stay away from sensitive topics. When she founded a rival publication, Caixin, 90 per cent of Caijing’s editorial staff left to join her. She has been called the most dangerous woman in China.

Relationship with the government: Complicated. Caijing is published by the official Stock Exchange Executive Council, which probably gave Ms. Hu some protection from the censors while she was there. She maintains a powerful network of allies. And, like Han Han, she knows where the lines are drawn, even as she tries to move them. As The New Yorker noted, “when she criticizes [the government], either in her column or in her editing choices, she uses the language of loyal opposition.”

Impact: Significant. While human rights and democracy have gone backward in the past 20 years, China’s media scene has improved dramatically. The boundaries of what you can say in China are moving fast, and much credit belongs to Ms. Hu.

Where she will be on Dec. 10: Probably at her desk, trying to decide what she can or can’t publish. Some topics, such as Mr. Liu’s Nobel Peace Prize, seem too sensitive even for her.

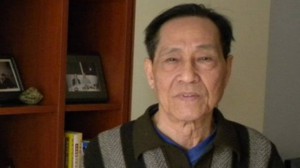

Li Rui

Born 1917.

What makes him a dissident: Mr. Li knows from an insider’s perspective what has gone wrong with the Communist Party of China. He was a personal secretary to Mao Zedong in the 1950s before being sentenced to two years in a labour camp for questioning the human costs of the disastrous Great Leap Forward. Upon his release, he rejoined the party and rose again to become a vice-minister and deputy head of the powerful Organization Department. Upon retirement, however, he returned to the role of critic and has published a series of open letters calling for change, including one this year that called for an end to official censorship. That missive, published in October, was seen as an attempt to support Premier Wen Jiabao in his efforts to reform the party from within.

Relationship with the government: Mr. Li clearly still has powerful friends. Despite his public attacks on the leadership, he maintains a home in Ministers’ House, an exclusive apartment block for retired top officials in Beijing. That he publishes open criticism of the government without any apparent penalty is a sign of lingering respect, if not affection, for one of the party’s elder statesmen.

Impact: Few ordinary Chinese are aware of Mr. Li’s activities because his letters, including the one about censorship, have never appeared in the official press. However, his stature gives him influence inside the party, and the censorship letter is believed to have fuelled debate at the recent plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: Mr. Li’s wife, Zhang Yuzhen, said by telephone that her 93-year-old husband is in poor health but was “very glad” Mr. Liu had won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Ding Zilin

Born in 1936 in Shanghai. Lives with her husband in Beijing. A portrait of their son, Jiang Jielian, killed during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, hangs in their home.

What makes her a dissident: After her only son was shot in the back by soldiers on the night of June 3, 1989, she went on the offensive, and along with other bereaved parents formed a group called the Tiananmen Mothers, which has spent the past two decades pushing for a full accounting of what happened that night on Beijing’s central square.

Relationship with the government: Hostile. The former philosophy professor and her husband, Jiang Peikun, live under constant surveillance. Mr. Liu has argued in the past that Ms. Ding and the Tiananmen Mothers should win the Nobel Peace Prize for their work.

Impact: By Ms. Ding’s own admission, the Tiananmen Mothers have failed in their mission. Before the 20th anniversary of the crackdown, she complained to The Globe and Mail that today’s generation of young Chinese do not care about what happened to her son and his classmates. “It’s pitiful, the materialism and practicality that has replaced idealism today. This is a real tragedy,” she said. “But in my mind, we cannot blame the young people too much. The root of the problem is the Communist Party. They made it policy to mislead the people for 20 years.”

Where she will be on Dec. 10: Unknown. Ms. Ding and Mr. Jiang have been unreachable since shortly after Mr. Liu won the Nobel Prize. It is believed that they are under house arrest, or have been forced to move to a location outside Beijing, as they were during the 2008 Olympics.

Born 1932 in coastal Zhejiang province.

What makes him a dissident: In the late 1980s, he was one of the most powerful people in the country, as both the director of the Office of Political Reform and a top adviser to then-party chief Zhao Ziyang. Amid the 1989 Tiananmen protests, Mr. Zhao asked Mr. Bao to draft a speech expressing sympathy with the students and support for some of their causes. It was a speech that split the Politburo, sparking a power struggle that the reformers lost. Within weeks, Mr. Zhao had been ousted, Mr. Bao jailed and the protests violently dispersed by soldiers and tanks. Since his release in 1997, Mr. Bao has been under house arrest, but that has not stopped him from signing the Charter 08 manifesto or (it’s believed) helping to spirit audiotapes made by Mr. Zhao to Hong Kong, where they formed the basis of a memoir published after he died.

Relationship with the government: Hostile on the surface, but in an interview last year with The Globe and Mail, Mr. Bao suggested that he still has powerful friends within the party establishment.

Impact: Like Ms. Ding, Mr. Bao worries that the past two decades have been lost as a generation has grown up “brainwashed.” He is also critical of foreign governments that have dropped their concern for human rights and democracy and China in the name of trade. “But I believe that as long as society is unfair, as long as there is inequality, people will chase freedom and democracy,” he said.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: Unknown. Like Ms. Ding and Ms. Liu, he has been unreachable since shortly after Mr. Liu won the Nobel Prize.

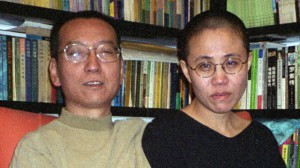

Liu Xiaobo

Born in 1955 in the northeastern city of Changchun. Married to fellow dissident Liu Xia.

What makes him a dissident: The former professor has been a leader of the pro-democracy movement since he joined his students protesting on Tiananmen Square in 1989. He has been jailed three times since then, and was one of the driving forces behind the publication of Charter 08, the manifesto advocating freedom of speech, human rights and the election of public officials.

Relationship with government: Adversarial in the extreme. Mr. Liu touched a nerve with Charter 08, which was based on Charter 77, a document that became a rallying point for those opposed to communist rule in the former Czechoslovakia. By singling out Mr. Liu for punishment from among Charter 08’s 300-plus original signatories (more than 10,000 have since signed an online version), the Chinese regime made it clear it views Mr. Liu as the Vaclav Havel of China.

Impact: Mr. Liu’s Peace Prize creates a major headache for China’s rulers, someone for their opponents to rally around. But Mr. Liu isn’t yet Mr. Havel or Aung San Suu Kyi. Most Chinese have never heard of him, or know only the caricature that the government has painted of Mr. Liu: an unpatriotic citizen who receives foreign money to stir up trouble in China. (As a past president of Independent Chinese PEN, he draws a salary subsidized by the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy.)

Where he will be on Dec. 10: Unless the Chinese government has a dramatic change of heart, Mr. Liu will be in his prison cell, having reportedly rejected an offer to be released into exile in exchange for a signed confession. His wife has also been under house arrest for two months.

Hu Jia

Born in 1973 in Beijing. Married to fellow dissident Zeng Jinyan.

What makes him a dissident: Mr. Hu is an environmentalist, an AIDS activist and the director of the June Fourth Heritage & Culture Association. He is currently serving a 3½-year sentence on the same “inciting subversion” charge as Mr. Liu and was also rumoured several times in recent years to be a finalist for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Relationship with government: Hostile. Mr. Hu’s sentence was meant to scare his fellow dissidents into silence, but it wasn’t enough to stop Mr. Liu and others from drafting Charter 08. Thus, Mr. Liu’s longer jail term is seen as a much more severe message to the Communist Party’s opponents. The Aizhixing Institute of Health Education, an HIV/AIDS centre Mr. Hu is associated with, receives money from the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy, which can be enough to persuade Beijing that someone is a foreign agent.

Impact: Given his prominence, it will be interesting to see how the Communist Party treats Mr. Hu when his sentence expires in late 2011. If he is freed, he will arguably become the most important regime critic who is inside China and not in jail.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: In jail, amid reports that he is suffering from a liver condition. His wife’s passport has been confiscated, but she says she will try to watch the ceremony online. “You might think [Mr. Liu’s win] would hasten the construction of Chinese civil society. But I’m not so optimistic,” Ms. Zeng said in a telephone interview this week. “The government has never given up trying to control civil society and suppressing the democratic and progressive forces.”

Gao Zhisheng

Born in 1966 and grew up in a cave in Shanxi province.

What makes him a dissident: A one-time soldier in the People’s Liberation Army, Mr. Gao is a self-trained lawyer who shot to fame representing those who were wronged during China’s rapid shift from full-on socialism to one of the world’s wilder brands of capitalism, defending landowners against runaway developers and representing victims of medical malpractice. His passion for human rights made him an enemy of the government, however, as he took on cases defending Falun Gong practitioners, grassroots Christian churches and those whose land was expropriated to make way for Beijing’s 2008 Summer Olympics. He went missing in February, 2009, reappeared briefly a year later to say he would no longer criticize the government, then went missing again in the western province of Xinjiang in April, 2010. He has not been seen since.

Relationship with the government: In 2001, he was named by China’s Ministry of Justice as one of the country’s top 10 lawyers. He crossed from favoured son to enemy of the state around mid-2005, when he sent President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao a letter calling on them to end official discrimination against Falun Gong practitioners. After that he was jailed repeatedly and, he says, tortured on several occasions. He also survived a 2006 traffic accident that Amnesty International believes was an assassination attempt orchestrated by China’s secret services.

Impact: Mr. Gao obviously rattled the higher-ups in China’s Communist Party with his efforts to change the country through its own courts. He’s believed to be either dead or detained.

Where he will be on Dec. 10: Unknown.

ངོ་མ་ཁོང་རྣམས་ཚང་མ་རང་ཁེ་དོར་ནས་སྤྱི་པའི་བྱ་གཞག་ཆེད་དུ་རང་སྲོག་འབེན་ལ་བཙུགས་མཁན་ཤ་སྟག་རེད།

ད་དུང་བོད་པའི་ནང་ནས་པེ་ཅིང་གི་རྨི་ལམ་དཀྲོགས་མཁན། འོ་རེད། རྩོམ་པ་པོ་དགའ་ལྡན་གྲྭ་བག་གྲོ

པེ་ཅིང་གི་རྨི་ལམ་ངན་པ་དཀྲོགས་མཁན་བཅུ་པོའི་བསམ་དོན་བཟང་པོ་མྱུར་གྲུབ་ཤོག །